I'd started loving poetry when I was young because of the linguistic beauty of words, because of the way alliteration, rhyme and metre were pleasing to the ear. Even when we'd moved on from rhyming couplets and quartrains to free verse at St.Xavier's in Durgapur, we were taught to 'appreciate' the metaphors and similies, to note the clever use of puns and punctuations which broke the flow of narrative. Non-linearity, personification, choice of words - these were the things I noticed and enjoyed. Henry Chappels, my school teacher in seventh grade, encouraged my enthusiasm, and this is when I wrote my earliest poetry. It was very childish - I'd started, as I guess most do, by imitating form and rhyme from poems I'd already read.

Give to me the life I love,

Let the lave go by me,

Give the jolly heaven above

And the byway nigh me.

Bed in the bush with stars to see,

Bread I dip in the river

There's the life for a man like me;

There's the life for ever.

The Vagabond, R.L.Stevenson

It was only when semantics and pragmatics got involved that trouble started.

Somewhere around 2010, when I started thinking about the meaning of poetry, things changed. Reading poetry was a different experience, and writing it was now more challenging. Poetry had to mean something, and this something needed to be grave and serious in my head. I needed to do better, and at the ripe age of 16, full of fantastic utopian dreams, I somehow came to the conclusion that I needed to understand poetry better to write it better. The person encouraging me in high school, again, was an English teacher. Her name was Aparna Venson, and she spent too many hours reading my poems and telling me they were good even when both of us knew they weren't.

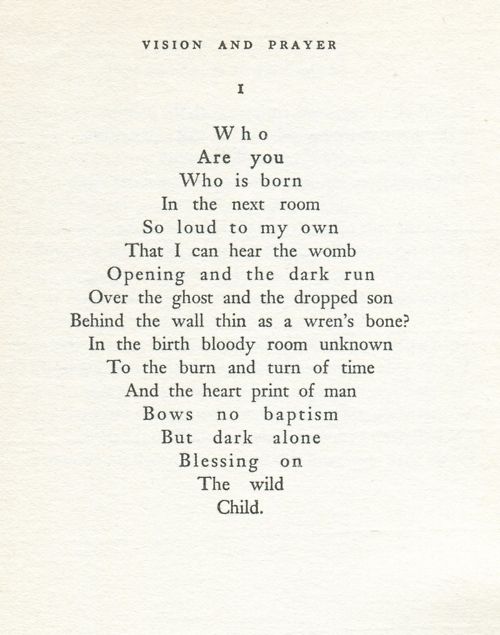

For a few years after, I struggled with this idea of reading and writing poetry, and have felt miserably isolated within the margins of a page I don't understand. I couldn't talk to poets whose works I read - they were all long gone, buried in graves in faraway countries. I used to sing Charge of the Light Brigade to myself, cycling from a Math tuition to a Hindi one in a small town in West Bengal. The Inchcape Rock was memorized and mumbled in sleep. The Road Not Taken was read and reread a hundred times from a school textbook. But how does one reach out to Tennyson or Southey or Frost? And the ones whom I knew from India - they were generations and social constructs apart from me - the inaccessible Vikram Seths of the country. I had no idea who was writing Indian poetry in English in 2012, no idea whom I could talk to about what I was writing. I had been fasttracked into the Indian rat race of procuring an engineering seat at a prestiguous college, and that didn't make it any easier. How do you talk about a drunk Welsh poet[1] with professors who want you to understand sp2 hybridisation?

So I wrote letters. To Vikram Seth, to Ruskin Bond, to Jug Suraiya[2], to addresses I'd pick off the back of the only literary magazine I knew, Indian Literature. These letters asked questions, almost pretentiously begging for guidance. For over six months, I received no reply. I didn't mind at first; it was fun sealing up yellow envelopes, sticking stamps on them, and sneaking them off to the Vidyanagar PO in Hyderabad. I was probably one of the very few 17 year olds who could navigate their way through a post office queue, and it was a quietly romantic experience. But it was discouraging after awhile for I had a lot of questions left unanswered.

My first reply did arrive, though, and it on the 25th of May, 2012, from Prof. Jayanta Mahapatra[3], a celebrated poet almost five times my age. Along with a letter, he sent me the last printed copy of Chandrabhaga, the literary journal he once edited. His letter was warm and concise, and I remember reading the square piece of paper while sitting at the foot of my bed. If you're ever received a personal letter, written in the thin composed hand of a person you've never met or seen before, you would know that such moments are hard to forget. It was a significant turn of events for me, perhaps one without which I would have probably given up on poetry. Jayanta 'Sir' would go on to humour me with more replies over the next year, before our correspondence stopped. He would try to tell me how poetry was born out of pain for him, and I would pretend to understand. ("Yes, of course we were pretentious -- what else is youth for?"). I remember nights when I would pore over the same page of Chandrabhaga, trying to understand what the words in the poems were doing, and what they were trying to convey:

His tongue drags to and fro

inside its crusted bell

to hit the right note.

This Won't Hurt, Adil Jussawalla

These were my first forays into modern Indian poetry in English - poems which talked about things that were directly around me - both tangible and intangible. You can relate more to poetry which is born of similar constructs in society (just the way you can relate more to poetry written in your mother-tongue, but that's another story[4]). And reading these poems in Chandrabhaga and Indian Literature, I had an endless array of questions.

It was also around this time that decided to go knock on Prof. Shiv K. Kumar's door. I'd come to know of him because of his poem Mother's Day in our English textbook, and I found out that he lived just behind my brother's old school. So on the afternoon of the 21st of January, 2013, armed with a couple of his books ( Losing My Way and Woolgathering ) and no money in my pockets - I ended up at Prof. Shiv K. Kumar's doorstep[5].

The old lady who opened the door eyed me from head to toe, suspiciously keeping her distance. "Yes?" she asked.

"Good afternoon, ma'am. Is this Prof. Shiv K. Kumar's house?"

A moment of silence, as she scrutinised my unkempt appearance once more.

"Yes, who are you?"

"My name is Sriharsh, I wrote to Prof. Kumar, twice. I want to be a poet."

She chuckled at this. "You want to be a poet?" she said, amused.

"Yes, ma'am. A poet."

More chuckling. "How old are you, again?"

"I'm 18, ma'am."

Silence.

"You could be a ruffian. I don't think I should let you in."

I'd walked quite a lot and was tired and thirsty, and was in such dire straits financially[6], that I couldn't afford to make this trip all the way across the city, again.

"I'm a student, ma'am, studying for IIT-JEE. I'm not a ruffian, please believe me. I've walked a long way, and am tired and thirsty."

"How do I know you're not a goonda? You look like one. How do I know you won't come in, beat up and rob us old people, and make away with all the valuables?"

I pulled out the two books on poetry I had, and showed them to her. Then I handed out my identity card, too, to her. She looked at them all, and then handed them back.

"Come in, quickly, but don't make too much noise. He doesn't like to be disturbed, it's nap time as it is."

We do it differently

in this dark continent.

Not just once a year

a string of spurious verses

ensconced in a bouquet

shaped like Chinese house of dreams.

Mother's Day, Shiv K. Kumar

Prof. Kumar, 91 at that time, waved the letters I'd written to him angrily at my face. "Who writes such long letters, eh? And in such small handwriting? Do you know how difficult it is to read your words?"

I didn't reply. I didn't think I was supposed to. I stared at my feet guiltily instead, like a truant caught red-handed in some inexcusable crime, now in front of the headmaster.

Prof. Kumar leaned back in his chair, annoyed. "Wants to be a poet, huh." He muttered to himself.

"I'm sorry, sir. I didn't think of it."

"You should, if you want to be a poet. Why do you want to, anyway? Do you know what it means to be a poet?"

I mumbled something about words and how I liked them. He cut me in between.

"You don't, see. Look around you - what do you see?"

There were steel racks all across the walls, filled with books. I was surrounded by a sea of hardbounds, paperbacks and newsletters.

"A lot of books, sir."

"Yes, a lot of books, and I've read all of them. I needed to. Poetry is about people, about the world around you. You need to read a lot of poetry and be able to feel emotions before you want to convey them. It's about perspectives." He looked at me, as if trying to gauge if I was following. "Give me the poems you've written."

I pulled out my sheets, and handed them over. Two of those poems would go on to be published in Indian Literature, but I didn't know. Prof. Kumar adjusted his glasses, and started reading. "Very raw. And lacks emotion," he said, five minutes later, handing me back the sheets. "You need to practise writing poetry, your technique is very weak, and your words don't really move me."

I nodded.

"But you do have the ability. Keep at it. Try to understand how you feel, and find ways to express it. Practise."

"Thank you, sir."

"Have you actually read my poems?"

"Sir, I - "

"You should read Which of my selves do you wish to speak to? Do you have a copy?"

"No, Sir, I don't."

"Then take mine. But I won't give it for free, it's the only copy I have left. Can you pay for it?"

I couldn't. I needed that money to get home.

"Yes, sir, I can."

The transaction was made, and Prof. Kumar gave me the contact details of another person he asked me to talk to.

"His name is Gopal, he'll help you with poetry. Contact him."

"Thank you, sir."

"Don't come to my house, again. I don't have the time."

"Yes, sir."

"And don't send me any more lenghty letters."

"Yes, sir."

I still remember the way he shuffled away to his bedroom while I left. Wants to be a poet, huh, he was muttering to himself.

I contacted Mr.Gopal, but he wasn't very interested in helping. JEE exams were looming, and I had already messed up my preparations. Prof. Jayanta Mahapatra hadn't replied in a while, either, and it was a long time before I would read or write poetry or try to reach out to other poets again. I spent the next year working on an unfinished fantasy fiction novel, stopped midway when my father was diagnosed with a terminal disease. Soon, I got an admit into IIIT, after which life swept me away down stranger paths. For a few years, I would stop writing and reading poetry, and stop calling myself a poet. I had lost an identity.

tomorrow, I tell myself,

I will find words,

as slender

as blades of grass,

and as large as the moon.

I will condense a lifetime

into a conversation.

tomorrow, yes.

but I'm scared that

by when I have such words, they

will all be left

unsaid

over a grave.

with my father, bhyrava

In late January 2017, my father passed away after a long fought battle with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. It was a difficult phase of my life and I will skip over the drawn-out parts, but two years later, I found catharsis in poetry, again.

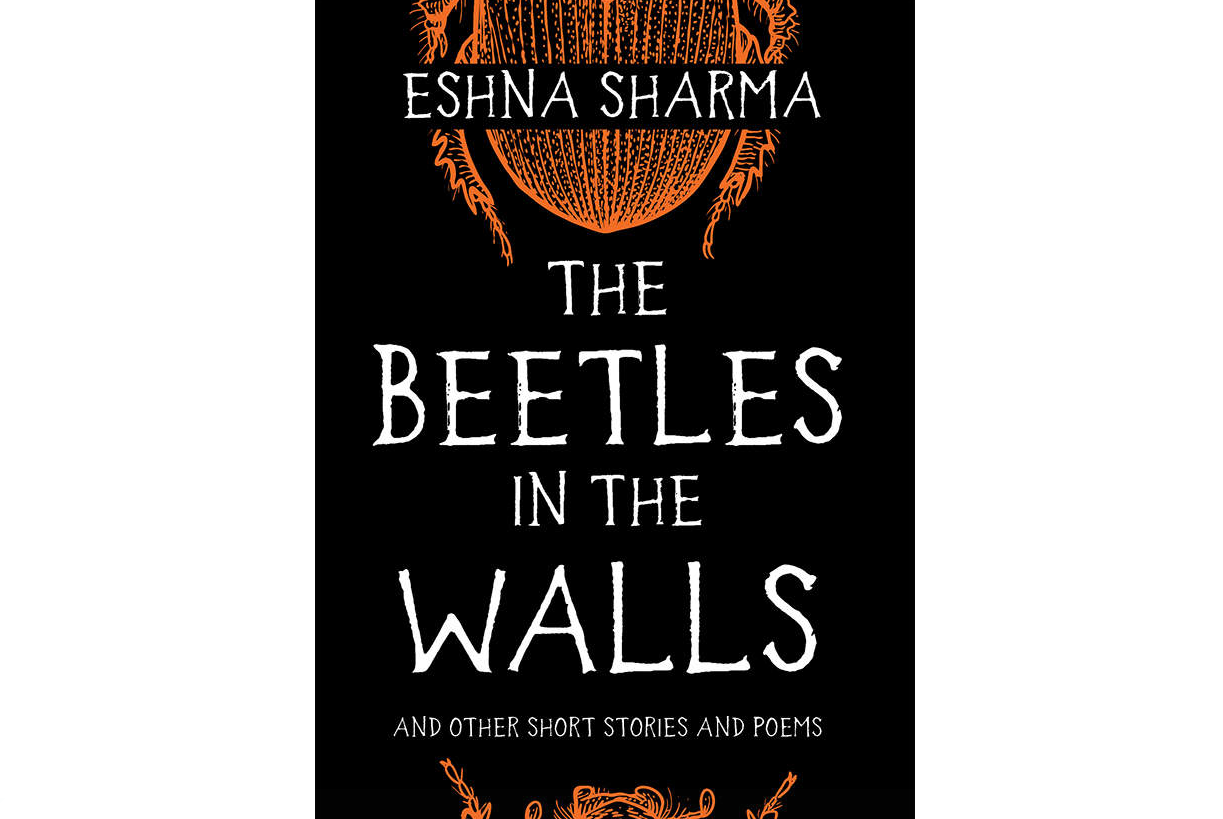

Somewhere in this time, I had the good fortune of striking up conversation with a wonderful Indian poet, Mihir Vatsa[7], whose works and words helped me in ways he would not know. I wrote poetry again because it helped, and some of my poems found their way into publication. Eventually, in May last year, it so happened that my first collection of poems found their way into the world. Identity, restored to an extent.

Today, on a hot April morning, I'm alone in my apartment in the midst of a month-long lockdown, juggling work from home, chores and anxiety that the pandemic has brought us all. I started looking back at my tale, and it felt like a good time to narrate it.

To quote Ruskin Bond, 'And when all the wars are over, a butterfly will still be beautiful'.

Dylan Thomas was a huge influence, I imitated the villanelle back then, and was inspired by his letters as well. Years later, as I sat outside the ICU unit a day before my father passed away, I would read out And Death Shall Have No Dominion aloud to my brother. ↩︎

Jug Suraiya actually replied. I had written to him in response to a TOI editorial piece on writing letters, and his reply - a scrawny bunch of lines on ruled paper - is something I've stashed away in a vault guarded by a dragon. ↩︎

Professor Jayanta Mahapatra's poetry can unnerve the casual reader. Not only was he prolific in his own writings, he spent a lot of time translating Oriya poetry into English, effectively defining an era of Indian poetry in English. Read a bit more here. ↩︎

There is another blog post in here, somewhere - I could on and on about the frustration one feels when he cannot express himself in the tongue that feels most comfortable to him. Colonialism, what have you done? ↩︎

A comedy of errors preceded this, however, where I ended up in the wrong Kakatiya Nagar of the city - there were apparently four of them. The auto driver who told me this in Tollychowki was laughing his head off at me and the printouts of the Google Maps I had in my hands -I had no internet-enabled phone back then. Good old times. ↩︎

I hadn't told my parents anything about this journey - or the books I bought, or the typewriter I'd purchased, or the money I spent on stationery for letters, or the money I'd spent on MMTS rides. I was truly broke. ↩︎

Mihir Vatsa is a winner of the Srinivas Rayaprol poetry award, and current publisher of the wonderful vayavya. ↩︎

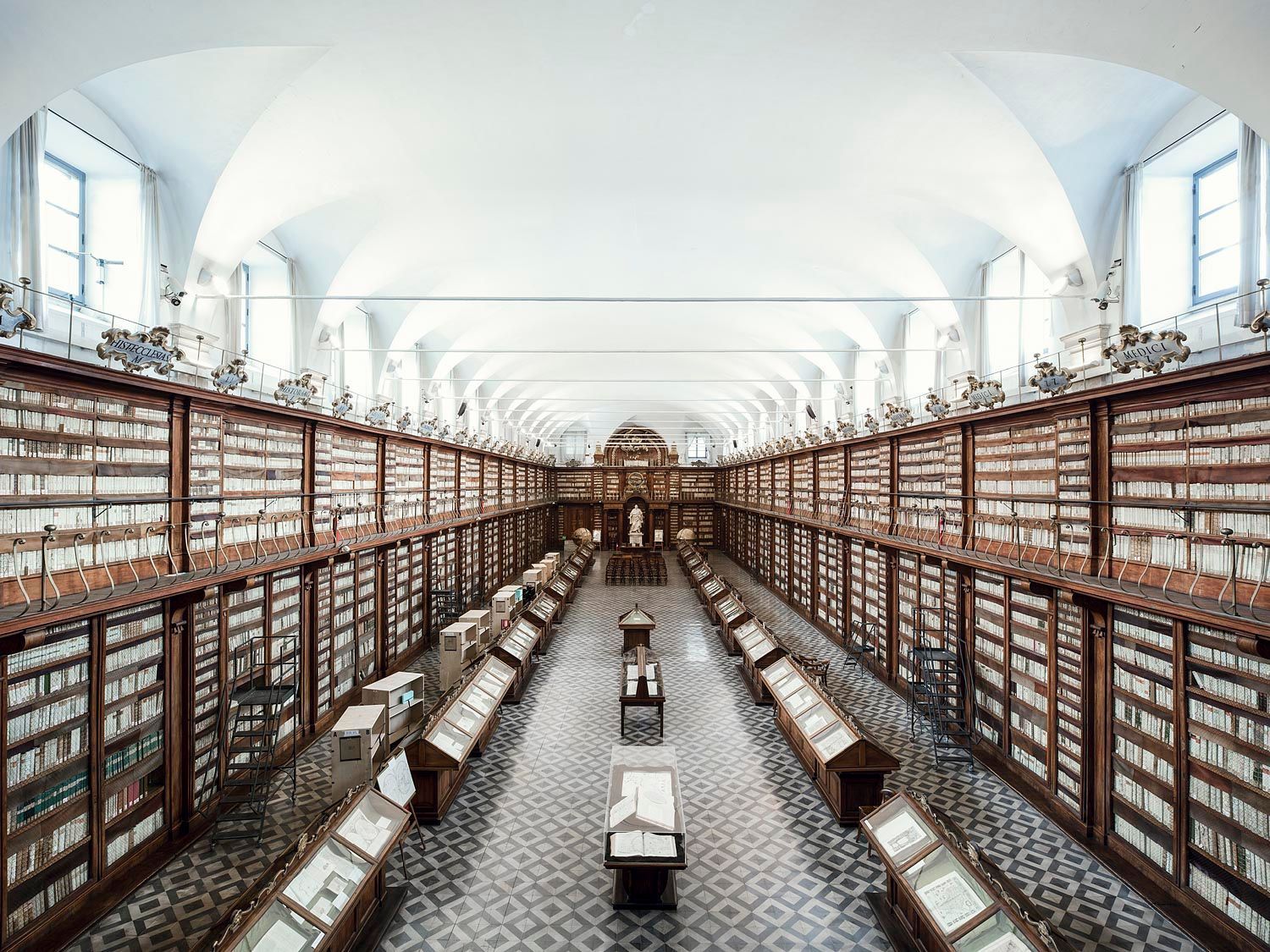

Cover: Biblioteca Casanatense, Rome by Thibaud Poirier